One of the things that was frequently missing from "Your Friends The Titanosaurs" was heads. Sure, there were a fair number of lower jaws and braincases, but actual faces were few and far between. Skulls just don't seem to have stuck with the rest of the skeleton, and in general were not made of the sternest material in a titanosaur's body. (Bitey parts of the skull, yeah, those are more robust. Braincases, yeah, those are knots of bone. Stuff in between? Not so much.) Several entire continents are unrepresented by reasonably complete titanosaur skulls. We can now scratch Australia off that list, thanks to Diamantinasaurus matildae, as described in great detail by Poropat et al. (2023).

(...or can we? See below!)

The specimen in question, AODF 0906 (Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum, Winton, Australia), comes from rocks of the Winton Formation at Elderslie Station in central Queensland, northeastern Australia, and represents the fourth individual assigned to D. matildae. Known informally as "Ann", AODF 0906 was found in two clusters separated by a few meters, one including pelvic bones and several hind leg bones, the other including the cranial bones and a couple of leg bones and ribs. Overall the specimen includes a partial skull and lower jaws, a possible ceratobranchial bone (part of the hyoid apparatus), five sacral centra and several sacral processes, the centrum of the first caudal, four dorsal ribs, a chevron, the left pelvis and right ischium, both hind legs above the ankles, a fragment probably belonging to the right astragalus, all five right metatarsals, five pedal phalanges of right toes 3 and 4, and fragments. The partial skull is most complete on the left side, which includes the only premaxilla, maxilla, lacrimal, frontal, parietal, and ectopterygoid. Both postorbitals, squamosals, qudratojugals, quadrates, and pterygoids are present, along with the braincase (Poropat et al. 2023). The only major facial bones that appear to be missing are the nasals and jugals.

|

| So as not to bury the lede any more than I already do: Poropat et al. (2023)'s overall reconstruction, clipped from Figure 3. Scale bar is 100 mm (3.94 in). CC BY 4.0. |

Not only is the skull mostly complete, but this is also D. matildae's first record of hind foot bones and, surprisingly, caudals (it seems like caudals are given away when new titanosaurs are named). D. matildae was already one of the best-represented titanosaurs, and AODF 0906 further solidifies that status. The species is a bit thin in total vertebrae, but we can't have everything.

|

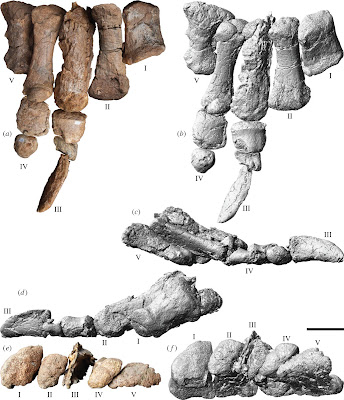

| Because how often do we have titanosaur feet around here? Figure 26 from Poropat et al. (2023). Scale bar is 100 mm (3.94 in). CC BY 4.0. |

The first thing you might notice about the skull when taken as a whole is that it looks not unlike the skull of Sarmientosaurus musacchioi, particularly in dorsal or ventral view, where the muzzle ends with a blunt point. This is not entirely unprecedented, as both species had previously been proposed as members of the clade Diamantinasauria. In side view D. matildae is not as quite as well-preserved, so there is some wiggle room about the exact profile of the face (it's been given a somewhat diplodocid-like profile, a bit more elegant than the "archless Giraffatitan" applied to S. musacchioi). Both, though, have long tooth rows and rather large teeth, and don't have as extreme of an arch in the jugal-quadratojugal area as later titanosaurs. D. matildae had four teeth per premaxilla, nine per maxilla, and 11 per dentary, a few teeth fewer than S. musacchioi for the maxilla and dentary. The two skulls are similar in size, with the D. matildae skull being slightly larger than the S. musacchioi skull. Dimensions are estimated as 500 mm long versus 250 mm wide versus at least 210 mm tall (19.7 by 9.84 by 8.27 inches) (Poropat et al. 2023).

|

| The entirety of Figure 3 (which see for lengthy caption). CC BY 4.0. |

A secondary question from the publication is less easily answered: is Diamantinasaurus (and other diamantinasaurs) a titanosaur? Poropat et al. present two analyses, one that has Diamantinasauria near the base of Titanosauria (equal weights), and another that has it a couple of notches outside of Titanosauria (extended implied weights). Fair enough: we're looking at something that's just inside or just outside, which is reasonable on the basis of age and the shape of the skulls of Diamantinasaurus and Sarmientosaurus. Diamantinasaurus shows some features that are not expected for a titanosaur, such as a sacrum with only five vertebrae and an amphicoelous first caudal. It also had three phalanges in the third toe, which is not extremely common among titanosaurs but not unknown (Epachthosaurus sciuttoi).

The problem, ultimately, is not Diamantinasaurus's fault; it's doing the best it can. In terms of material and overall coverage, it's doing better than 95% of titanosaurs. The problem, obviously, is everyone else. Complete sacra, good feet, and nearly complete skulls are hard to come by. I've got a spreadsheet that depicts which bones or bone groups are known for which titanosaurs. You probably don't need to hear it from me, but there are a lot of empty cells. How many complete sacra are known for other basal titanosaurs? Well, there's one for Dongyangosaurus (if you are confident that it is in fact a titanosaur) and Malawisaurus (if the sacrum in fact belongs to Malawisaurus). How many feet are known for other named basal titanosaurs? (crickets chirp) Admittedly, there are a few sacra and feet on the other side of the line, but you get the idea. More to the point, how many sacra, feet, and skulls are known for Andesaurus, the gatekeeper of Titanosauria? No dice: you get two (2) sacral vertebrae, no (0) bones of the hind feet, and no (0) head. This is, to put it mildly, inconvenient; basal titanosaurs really need to step up their game. Poropat et al. (2023) concluded by leaning in the "titanosaur" camp ("probably" versus "possibly" outside).

|

| The mystery of the undersacralized titanosaur? Clipped from Figure 22 in Poropat et al. (2023), scale bar 200 mm (7.87 in). CC BY 4.0. |

Reminder: I'll be giving a talk for the Geological Society of Minnesota on Monday, May 8: "Snorkeling at Shadow Falls: Fossils of Minnesota". Non-members are welcome!

References

Poropat, S. F., P. D. Mannion, S. L. Rigby, R. J. Duncan, A. H. Pentland, J. J. Bevitt, T. Sloan. and D. A. Elliott. 2023. A nearly complete skull of the sauropod dinosaur Diamantinasaurus matildae from the Upper Cretaceous Winton Formation of Australia and implications for the early evolution of titanosaurs. Royal Society Open Science 10(4):article 221618. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.221618.

No comments:

Post a Comment