We start off with two of the geologically oldest described titanosaurs before jumping back to the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia. If you're keeping track, you may notice that Titanosaurus seemingly should have been included. It's being held over for next month, which will be all Titanosaurus, including various species originally named to Titanosaurus that don't belong there and haven't otherwise been covered.

Tapuiasaurus macedoi

Tapuiasaurus macedoi has gotten into the news recently because the holotype happened to be laying on top of a theropod, which has now been described (Zaher et al. 2020). While we applaud the titanosaur's good sense in laying on a theropod (although admittedly there is no evidence that this is anything more than a chance association), this does leave it open to being overshadowed by its toothier companion, which would be unfortunate for a sauropod specimen which is more than mere theropod overburden.

|

| The skull of Tapuaisaurus macedoi (scale bar 10 cm). Figure 1 in Zaher et al. (2011). CC-BY-2.5. |

T. macedoi was named in Zaher et al. (2011) for MZSP-PV 807 (Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil), an associated and partially articulated partial skeleton including a nearly complete skull and lower jaw, hyoid bones, 7 cervicals (including atlas and axis), 5 dorsals, ribs, the left sternal, the right coracoid, the right humerus, both ulnae, the left radius, metacarpals, femora, the left fibula, and a nearly complete left hind foot (Zaher et al. 2011). The genus name includes a Jês word for tribes that lived in inner Brazil, while the species name honors Ubirajara Alves Macedo, who found the fossil-bearing site (Zaher et al. 2011), giving us something like "Ubirajara Alves Macedo's lizard of the Tapuia peoples." The specimen was found in the Embira-Branca Hills near Coração de Jesus City in Minas Gerais, Brazil. The stratigraphic unit is the Quiricó Formation, which Zaher et al. (2011) regarded as Aptian but Zaher et al. (2020) placed as slightly older, at the Barremian–Aptian boundary (see Navarro 2019 for a longer discussion of the issue).

|

| I don't think hyoids have ever come up in the blog before, so here are the ceratobranchials of Tapuiasaurus, part of its hyoid apparatus. The scale bar is 5 cm. Figure 3 in Zaher et al. (2011). CC-BY-2.5. |

|

| The quarry map and stratigraphy for the type specimen. Supplemental Figure 3 from Zaher et al. (2011), although I got this copy from Wikimedia Commons because of download issues. CC-BY-2.5. |

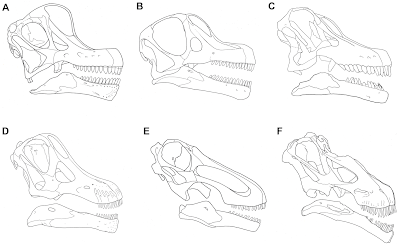

The skull and jaw have received the most thorough description to date, being the main focus of Zaher et al. (2011) and Wilson et al. (2016); the postcrania are currently only described in detail in a thesis (Navarro 2019), a portion of which is available online (but not the description part). The skull is somewhat skooshed by shearing and lateral compression, and in its current state measures about 0.5 m long (1.6 ft) (Wilson et al. 2016). Many of the skull bones are unfused and the sutures are easy to find (Wilson et al. 2016), so this individual was not fully grown. Overall, despite dating to the middle of the Early Cretaceous, the T. macedoi skull is much more like the skulls of late Late Cretaceous titanosaurs Nemegtosaurus mongoliensis and Rapetosaurus krausei than that of Sarmientosaurus musacchioi, from the early Late Cretaceous. The most immediately obvious points shared by Tapuiasaurus, Nemegtosaurus, and Rapetosaurus but not Sarmientosaurus are the skinny cylindrical teeth limited to the anterior part of the jaws and an enlarged antorbital fenestra. There are also several small openings between the antorbital fenestra and the teeth. There are 12 teeth per maxilla, 4 per premaxilla, and 15 per dentary. The jaws are not squared off as in some titanosaurs. (Incidentally, if you're curious what an squared-off antarctosaur-style skull looks like, there's a photo of an undescribed example under preparation here. It came up in the comments a couple of months ago, but is certainly worthy of being mentioned in a post!)

|

| One more time for Figure 33 in Martínez et al. (2016). Tapuiasaurus macedoi is F, in the company of Giraffatitan (A), Abydosaurus (B), Sarmientosaurus (C), Nemegtosaurus (D), and Rapetosaurus (E). CC-BY-4.0. |

For something known from such quality material, Tapuiasaurus has proven hard to pin down. In terms of relationships, T. macedoi,

which is almost always included in titanosaurian phylogenies, has taken

a leisurely cruise throughout Titanosauria since its description. It

shows some attraction for one or both of Nemegtosaurus and Rapetosaurus,

but is inconsistent with which one it gravitates towards, and at any

rate I'm suspicious that this is an effect of the small number of

titanosaur skulls (see also Wilson et al. 2016 for more on this issue).

Description of the postcrania may help stabilize it.

Tengrisaurus starkovi

We already saw Tengrisaurus starkovi once before, but it wouldn't do to leave it out of the party. T. starkovi is another Early Cretaceous form, this time hailing from what is now south-central Siberia. It was named in Averianov and Skutschas (2017). The genus name is a reference to the god Tengri of the pre-Buddhist/Christian/Islamic Turkic–Mongolian religion, while "starkovi" honors Alexey Starkov for his involvement in paleontology of the Transbaikal region (Averianov and Skutschas 2017), which works out to something like "Starkv's Tengri's lizard".

The type specimen is an anterior caudal, ZIN PH 7/13 (Paleoherpetological Collection of the Zoological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences). Middle caudal ZIN PH 8/13 and anterior caudal ZIN PH 14/13 were found within a few meters of the type specimen and have been assigned to T. starkovi, potentially representing the same individual (Averianov and Skutschas 2017). ZIN PH 8/13 beat the type specimen to print by a couple of decades, being mentioned in Nesov and Starkov (1992) and Nesov (1995), although it's not as if the type had a chance, having only been found in 1998 (Averianov and Skutschas 2017). These caudals were found in the Mogoito Member of the Murtoi Formation (Barremian–Aptian), at Mogoito on the west side of Gusinoe Lake in Buryatia, Russia (Averianov and Skutschas 2017). Sauropod remains have been reported from the Murtoi Formation of Mogoito since the 1960s, amounting to caudals, teeth, a scapula and a rib (see Averianov and Skutschas 2017 for citations). Most intriguingly, two pieces of dinosaurian armor were reported by Nesov and Starkov (1992), but these specimens could not be found by Averianov and Skutschas, so it's not known if they belonged to a titanosaur or thyreophoran.

Averianov and Skutschas (2017)'s phylogenetic analysis placed Tengrisaurus and its procoelous caudals not only within Titanosauria, but within the more exclusive titanosaur clade Lithostrotia. While I'm skeptical of most of the proposed internal arrangements of Titanosauria, the implication that T. starkovi is fairly derived is certainly interesting considering how few other named titanosaurs are as old. Some other putative early titanosaurs have fallen by the wayside, but T. starkovi has so far remained a titanosaur, although to be fair it hasn't had much time to percolate into the literature beyond name checks. It shows up in the phylogenetic analysis of Averianov and Efimov (2018) with a revised coding but similar position. Wilson et al. (2019) reported one of the Tengrisaurus caudals as most similar to a titanosaur caudal from the much younger Lameta Formation of India.

Traukutitan eocaudata

Traukutitan eocaudata is one of the more obscure titanosaurs, although it does have a paper trail predating many of the other members of the group. It was first reported in Salgado and Calvo (1993) under the catalog number of the only known specimen, MUCPv 204 (Museo de la Universidad Nacional del Comahue, Paleovertebrate collection). At this time the specimen consisted of 10 incomplete caudal vertebrae, both femora, and fragments of the pubis. It did not receive formal description until Juárez Valieri and Calvo (2011), by which time three more caudals were attributed to MUCPv 204, but the pubic fragments had gone missing. As reported in Salgado and Calvo (1993), the locality was in the Río Colorado Formation at Loma de la Lata in Neuquén, Argentina; by 2011 the stratigraphy had been refined to the basal Bajo de la Carpa Formation of the Río Colorado Subgroup, and the locality had become known as Sitio Trauku (Juárez Valieri and Calvo 2011). The genus name refers to the Araucanian mountain spirit Trauku, and the species name refers to the middle caudals, which are not strongly procoelous and are therefore regarded as not derived (Juárez Valieri and Calvo 2011); therefore, the name translates as something like "Trauku's early-tailed titan."

The feature which had originally drawn attention to MUCPv 204 is the articulation of the caudals. Specifically, the anterior caudals are strongly procoelous, as is seen in most titanosaurs. The middle caudals are variously described as "amphyplatyan," flat on both ends of the centrum (Salgado and Calvo 1993), or "procoelous-opisthoplatyan," concave anteriorly and flat posteriorly (Juárez Valieri and Calvo 2011). The distinction is a bit fine, but the point is these caudals don't have typical titanosaur articulations. The neural arches of all caudals are cheated to the anterior half of the centra (Salgado and Calvo 1993), as in other titanosaurs. The femora are large, at 1.85 m long (6.07 ft) (Salgado and Calvo 1993; it can be safely assumed that "1.85 cm" is a typo). None of the neural arches are complete, though, so perhaps there was some more growing to do? The femora are of intermediate robustness among titanosaurs (González Riga et al. 2019).

|

| Titanosaur femora, illustrated at the same length. Traukutitan eocaudata is "l" (a typo in the figure caption has it as "j"). (Figure 7 in González Riga et al. 2019). CC-BY-4.0. |

Juárez Valieri and Calvo (2011) did not include a phylogenetic analysis in their description, nor has T. eocaudata been popular in published phylogenies. They did draw attention to some similarities with Futalogknosaurus and Mendozasaurus, and suggested that T. eocaudata

could be a lognkosaur. The only phylogeny I've seen it come up in is in

the Sassani and Bivens (2017) preprint, where it shows up around Drusilasaura and Dreadnoughtus on the line leading to the lognkosaurs.

References

Averianov, A., and P. Skutschas. 2017. A new lithostrotian titanosaur (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Early Cretaceous of Transbaikalia, Russia. Biological Communications 62(1):6–18. doi:10.21638/11701/spbu03.2017.102.

Averianov, A., and V. Efimov. 2018. The oldest titanosaurian sauropod of the Northern Hemisphere. Biological Communications 63(6):145–162. doi:10.21638/spbu03.2018.301.

González Riga, B. J., M. C. Lamanna, A. Otero, L. D. Ortiz David, A. W. A. Kellner, and L. M. Ibiricu. 2019. An overview of the appendicular skeletal anatomy of South American titanosaurian sauropods, with definition of a newly recognized clade. Academia Brasileira de Ciências 91(Supp. 2): e20180374. doi:10.1590/0001-3765201920180374.

Juárez Valieri, R. D., and J. O. Calvo. 2011. Revision of MUCPv 204, a Senonian basal titanosaur from northern Patagonia. Pages 143–152 in J. Calvo, J. Porfiri, B. González Riga, and D. Dos Santos, editors. Paleontología y dinosaurios desde América Latina. EDIUNC, Mendoza, Argentina.

Martínez, R. D. F., M. C. Lamanna, F. E. Novas, R. C. Ridgely, G. A. Casal, J. E. Martínez, J. R. Vita, and L. M. Witmer. 2016. A basal lithostrotian titanosaur (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) with a complete skull: implications for the evolution and paleobiology of Titanosauria. PLoS ONE 11(4):e0151661. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0151661.

Navarro, B. A. 2019. Postcranial osteology and phylogenetic relationships of the Early Cretaceous titanosaur Tapuiasaurus macedoi Zaher et al. 2011. Master's dissertation. Instituto de Biociências da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil.

Nesov, L. A. 1995. Dinozavry Severnoi Evrazii: novye dannye o sostave kompleksov, ekologii i paleobiogeografii [Dinosaurs of Northern Eurasia: New Data about Assemblages, Ecology and Paleobiogeography]. Izdatelstvo Sankt-Peterburgskogo Universiteta, Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Nesov, L. A., and A. I. Starkov. 1992. Melovye pozvonochnye iz Gusinoozerskoi kotloviny Zabaikalya i ikh znachenie dlya opredeleniya vozrasta i uslovii obrazovaniya otlozhenii [Cretaceous vertebrates of the Gusinoe Lake Depression in Transbaikalia and their contribution into dating and determination of sedimentation conditions]. Geologiya i Geophysica 6:10–19.

Salgado, L., and J. O. Calvo. 1993. Report of a sauropod with amphiplatyan mid-caudal vertebrae from the Late Cretaceous of Neuquén province (Argentina). Ameghiniana 30:215–218.

Sassani, N., and G. T. Bivens. 2017. The Chinese colossus: an evaluation of the phylogeny of Ruyangosaurus giganteus and its implications for titanosaur evolution. PeerJ Preprints 5:e2988v1. doi:10.7287/peerj.preprints.2988v1.

Wilson, J. A., D. Pol, A. B. Carvalho, and H. Zaher. 2016. The skull of the titanosaur Tapuiasaurus macedoi (Dinosauria: Sauropoda), a basal titanosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 178(3):611–662.

Wilson, J. A., D. M. Mohabey, P. Lakra, and A. Bhadran. 2019. Titanosaur (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) vertebrae from the Upper Cretaceous Lameta Formation of western and central India. Contributions of the Museum of Paleontology, University of Michigan 33(1):1–27.

Zaher, H., D. Pol, A. B. Carvalho, P. M. Nascimento, C. Riccomini, P. Larson, R. Juarez-Valieri, R. Pires-Domingues, N. J. da Silva, Jr., and D. de Almeida Campos. 2011. A complete skull of an Early Cretaceous sauropod and the evolution of advanced titanosaurians. PLoS ONE 6(2):e16663. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0016663.

Zaher, H., D. Pol, B. A. Navarro, R. Delcourt, and A. B. Carvalho. 2020. An Early Cretaceous theropod dinosaur from Brazil sheds light on the cranial evolution of the Abelisauridae. Comptes Rendus Palevol 19(6):101–115. doi:10.5852/cr-palevol2020v19a6.

No comments:

Post a Comment