Last week's publication of the stem-caecilian Funcusvermis reminded me that I really ought to show off Petrified Forest National Park (PEFO) more often. Since the last spotlight, on the "biloph" trilophosaur Trilophosaurus phasmalophus in spring 2020, four more species of Triassic vertebrates have been described from fossils found in the park, to go along with a bushel of reports on anatomy, identifications of rare forms, vertebrate trace fossils, stratigraphy and geochronology, and other topics, to say nothing of conference abstracts and papers that mention PEFO fossils in wider contexts. (SVP conferences are usually good for a handful of PEFO topics.) Because we're talking the Late Triassic, the taxonomic diversity is wide. There's a little bit of almost everything.*

*Interestingly enough, that includes Paleozoic marine invertebrates: reworked fossiliferous cobbles of the Permian Kaibab Formation have been found in the park's Chinle Formation outcrops, particularly the Sonsela Member. There are also limited Neogene deposits with Hemphillian vertebrates.

Classically, as with most places that have produced vertebrate fossils for more than a century, big singular fossils were long the focus (e.g., skulls of phytosaurs). Although there is still interest in those kinds of fossils, increasingly study has focused on bonebeds and microvertebrates, with much more care given to stratigraphic placement. It turns out that PEFO holds a whole weird and wonderful landscape of everything that gave it a go in the Late Triassic, before a couple of groups of archosaurs took over land management for the rest of the Mesozoic. (And if you don't like vertebrates, the plants are just about as wild in their own way, and there are freshwater and terrestrial invertebrates as well.) It practically begs for a book like those on Florissant, Fossil Lake, the Morrison, and the White River Badlands.

|

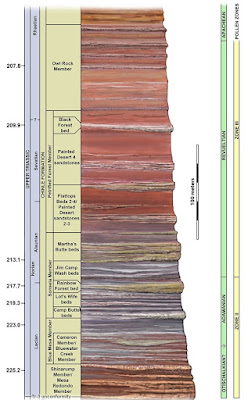

| Here's a strat column to help keep the geologic units straight, borrowed from the park website. |

With all of that in mind, here are a few quick hits from the past few years of research at PEFO:

Aetosaurs and friends: Aetosaurs are among the park's most iconic fossil vertebrates (an aetosaur was the star of the 2014 National Fossil Day logo for PEFO). One of the best-known aetosaurs is Typothorax. In 2021, Reyes et al. described a complete skull of Typothorax found in the Owl Rock Member in the park. The skull, the first known for the genus, has a distinctly upturned and rather dainty snout, and bears premaxillary teeth unlike some aetosaurs. It is proportionally small as far as aetosaur skulls go (Reyes et al. 2021).

Research and new specimens have introduced several cousins to Aetosauria. Marsh et al. (2020) described new material of the previously enigmatic Acaenasuchus geoffreyi from upper Blue Mesa Member localities in the Dinosaur Ridge area. It turns out to be something that's almost but not quite an aetosaur. Something else that turned out to be almost but not quite an aetosaur, after a more rambling path out of Dinosauria, is Revueltosaurus callenderi. The long-anticipated osteology of this species was published last year (Parker et al. 2022), showing it to have had a proportionally large, short, fat head with large leaf-shaped teeth, short neck and limbs, armor on the back and belly, and a sheath of osteoderms on the tip of the tail. At least 12 partially grown individuals were found in one quarry.

Amphibians: I would be remiss not to mention the inspiration for this post, the stem-caecilian Funcusvermis gilmorei (Kligman et al. 2023). The unusual name recognizes the 1973 funk hit "Funky Worm". Caecilians today are limbless amphibians, but the Funky Worm of the Chinle hadn't quite ditched its limbs, based on the presence of a fossil femur. It is known from material belonging to at least 76 individuals, discovered at Thunderstorm Ridge in the upper Blue Mesa Member. As such, it is a sterling example of the things that can found by working with microvertebrate material.

Azendohsaurs: Azendohsaurs are one of several varieties of Triassic reptiles that used to be dinosaurs but then decided there was more of a future (well, past, really) in turning out to be something else entirely. In their case, it was an alliance with trilophosaurs; imagine a low-rider (sprawling) prosauropod and you'll get the general idea. Azendohsaurs were recently recognized in the Chinle Formation, and one form has been described from PEFO: Puercosuchus traverorum (Marsh et al. 2022). This genus and species is based on a right premaxilla and maxilla but is represented by bonebed material from at least eight individuals in the park, plus another bonebed near St. John. Both are in the upper Blue Mesa Member. One effect of the large sample size is the reidentification of various other bones, especially at the St. John site. These include a fair number of putative dinosaur bones, which just goes to show you can't trust an isolated Late Triassic bone. Marsh et al. also noted the interesting propensity for azendohsaurs to show up in bonebeds.

Cynodonts: The most famous mammalian cousin of the Chinle Formation is the big, stocky, tusked Placerias, but this is not what all Chinle therapsids were like. Kligman et al. (2020) described a much smaller cynodont from the upper Blue Mesa Member at Thunderstorm Ridge in PEFO. Named Kataigidodon venetus, it is known from a couple of partial dentaries. While not as imposing as Placerias (it probably looked more like a diminutive mole-rat), this species was much closer to the line that led to true mammals.

Dinosaurs and friends: One of the themes of dinosaur paleontology in the 21st century is that good Triassic dinosaurs can be hard to find. Isolated bones and teeth are especially likely to be incorrectly identified, in part because every darn thing around at the time had at least one or two features that are easy to mistake as dinosaurian. The problem seems to be especially pronounced in North America, where the record is, er, not as inspiring as on other continents. Nevertheless, they are out there. According to Marsh and Parker (2020), there were 50 dinosauromorph specimens known from the park at that time, 32 of which had been found since 2000. The great majority belong to small theropods, and only one can be assigned to a genus or species (the holotype of Chindesaurus bryansmalli). (A couple may have come from lagerpetids, which have more recently tended to be allotted to the pterosaur side of Ornithodira.)

Doswellids: Doswellia is not the easiest thing to describe quickly; it's a bit like a square-sided monitor lizard with a lot of armor and a champsosaur head. Parker et al. (2021) described the first occurrence of this genus from PEFO and the Chinle Formation in general, based on a few vertebrae and osteoderms found in the upper Blue Mesa Member (I'm sensing a theme here). They assigned the material to D. cf. D. kaltenbachi, marking the youngest occurrence of the species and in fact jumping it right straight out of its previous, more restrictive biostratigraphic assignment.

Drepanosaurs: The Chinle has proven to be great for drepanosaur diversity, with Jenkins et al. (2020) citing four different forms: Ancistronychus paradoxus (itself named from PEFO a few years ago), Dolabrosaurus aquatilis, Drepanosaurus sp., and their new genus and species Skybalonyx skapter, another Thunderstorm Ridge/upper Blue Mesa Member special. (What is a drepanosaur? It's kind of like a chameleon with a birdy head and an inability to decide whether it should be adapted for living in trees, swimming, or burrowing.) This new taxon was described from hand claws interpreted as used for digging. With a genus name meaning "dung claw" (in reference to its presence in the "coprolite facies"), it is also the second extinct reptilian from an NPS unit with a dung reference in its name, which is honestly kind of strange. (The only reason I know this is because the other one also showed up in a post; it was Coprophis dakotaensis.)

Paleoecology: I've focused on vertebrates here, but of course fossil plants are right there in the name of Petrified Forest National Park. Byers et al. (2020) published on evidence of fire scarring in 13 logs found in the park, focusing on a specimen from the Black Forest Bed of the upper Petrified Forest Member in order to describe the physical characteristics visible to the eye and present in thin sections. This conifer showed features typical of drought events in an area of short-term climate variability (years), with low-intensity fires.

Stratigraphy and geochronology: As I mentioned, refining the stratigraphic knowledge of the Chinle Formation has been a major concern at PEFO. The Colorado Plateau Coring Project has been one facet of this work, using information from deep cores to characterize the rocks. Magnetochronology of the Chinle Formation in PEFO (Core 1A) was published in Kent et al. (2019). In a natural extension, Haque et al. (2021) analyzed the underlying Moenkopi Formation in two cores from PEFO. The Moenkopi, although not vastly older than the Chinle, represents a noticeably different setting. Actually, it represents many settings, from evaporitic deposition to coastal mud flats to shallow coastal marine carbonates, and it varies substantially across its depositional area from western Colorado to southwestern California. What's interesting is that the Moenkopi turns out to include younger rocks than generally assumed based on marine correlations. Historically it has been attributed to the Early Triassic (not that the Early Triassic has ever been much more than a sneeze in the geologic time scale). At PEFO, the magnetic polarities of the Moenkopi look squarely Anisian (first half of the Middle Triassic). The overall Moenkopi thus appears to span from the Early Triassic into the Middle. (and anyway it makes sense that the formation's range would constrict and skew younger going away from the marine basin on the northwest.)

Meanwhile, Rasmussen et al. (2020) presented a radioisotope study of detrital zircon crystals from the 1A core. Among their conclusions is that there is no evidence for Carnian rocks at PEFO, and that therefore the Adamanian–Revueltian faunal turnover observed in the Sonsela Member is 10+ million years too young to be related to the Carnian–Norian boundary of about 227 million years ago. Hayes et al. (2020), also studying the faunal turnover, found that the turnover was protracted, and therefore not compatible with an attribution to the 215.4 million-year-old Manicouagan impact in Canada.

Trace fossils: With all of these animals running around, one might expect they interacted with each other from time to time. Most of these interactions are not conducive to fossilization, but there are exceptions. Gordon et al. (2020) published a bone mass from the Owl Rock Member of PEFO, made up of bones of Revueltosaurus. They interpreted this as a regurgialite (i.e., puked up like an owl pellet) rather than a coprolite for several reasons, include the absence of phosphate, scarcity of acid etching marks, and presence of muscle tissue. Exactly what produced it is not known, as there are multiple candidates for consuming an inoffensive revueltosaur. Drymala et al. (2021) looked at a trace produced at the other end of the consumption process. They described bite marks on an aetosaur osteoderm from the Sonsela Member, probably produced by a phytosaur or large croc cousin (e.g., Postosuchus).

References

Byers, B. A., L. DeSoto, D. Chaney, S. R. Ash, A. B. Byers, J. B. Byers, and M. Stoffel. 2020. Fire-scarred fossil tree from the Late Triassic shows a pre-fire drought signal. Scientific Reports 10(1):20104. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77018-w.

Drymala, S. M., K. Bader, and W. G. Parker. 2021. Bite marks on an aetosaur (Archosauria, Suchia) osteoderm: assessing Late Triassic predator-prey ecology through ichnology and tooth morphology. Palaios 36(1):28–37. doi: https://doi.org/10.2110/palo.2020.043.

Gordon, C. M., B. T. Roach, W. G. Parker, and D. E. G. Briggs. 2020. Distinguishing regurgitalites and coprolites: a case study using a Triassic bromalite with soft tissue of the pseudosuchian archosaur Revueltosaurus. Palaios 35(3):111–121. doi: https://doi.org/10.2110/palo.2019.099.

Haque, Z., J. W. Geissman, R. B. Irmis, P. E. Olsen, C. Lepre, H. Buhedma, R. Mundil, W. G. Parker, C. Rasmussen, and G. E. Gehrels. 2021. Magnetostratigraphy of the Triassic Moenkopi Formation from the continuous cores recovered in Colorado Plateau Coring Project Phase 1 (CPCP-1), Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona, USA: Correlation of the Early to Middle Triassic strata and biota in Colorado Plateau and its environs. JGR Solid Earth 126(9):e2021JB021899. doi: https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JB021899.

Hayes, R. H., G. Puggioni, W. G. Parker, C. S. Tiley, A. L. Bednarick, and D. E. Fastovsky. 2020. Modeling the dynamics of a Late Triassic vertebrate extinction: the Adamanian/Revueltian faunal turnover, Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona, USA. Geology 48(4):318-322. doi: https://doi.org/10.1130/G47037.1.

Jenkins, X. A., A. C. Pritchard, A. D. Marsh, B. T. Kligman, C. A. Sidor, and K. E. Reed. 2020. Using manual ungual morphology to predict substrate use in the Drepanosauromorpha and the description of a new species. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 40(5):e1810058. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2020.1810058.

Kent, D. V., P. E. Olsen, C. Lepre, C. Rasmussen, R. Mundil, G. E. Gehrels, D. Giesler, R. B. Irmis, J. W. Geissman, and W. G. Parker. 2019. Magnetochronology of the entire Chinle Formation (Norian age) in a scientific drill core from Petrified Forest National Park (Arizona, U.S.A.) and implications for regional and global correlations in the Late Triassic. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 20(11):4654–4664. doi: https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GC008474.

Kligman, B. T., A. D. Marsh, H.-D. Sues, and C. A. Sidor. 2020. A new non-mammalian eucynodont from the Chinle Formation (Triassic: Norian), and implications for the early Mesozoic equatorial cynodont record. Biology Letters 16(11):20200631. doi: https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2020.0631.

Kligman, B. T., B. M. Gee, A. D. Marsh, S. J. Nesbitt, M. E. Smith, W. G. Parker, and M. R. Stocker. 2023. Triassic stem caecilian supports dissorophoid origin of living amphibians. Nature. doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05646-5.

Marsh, A. D., and W. G. Parker. 2020. New dinosauromorph specimens from Petrified Forest National Park and a global biostratigraphic review of Triassic dinosauromorph body fossils. PaleoBios 37. doi: https://doi.org/10.5070/P9371050859.

Marsh, A. D., M. E. Smith, W. G. Parker, R. B. Irmis, and B. T. Kligman. 2020. Skeletal anatomy of Acaenasuchus geoffreyi Long and Murry, 1995 (Archosauria: Pseudosuchia) and its implications for the origin of the aetosaurian carapace. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 20(4):e1794885. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2020.1794885.

Marsh, A. D., W. G. Parker, S. J. Nesbitt, B. T. Kligman, and M. R. Stocker. 2022. Puercosuchus traverorum n. gen. n. sp.: a new malerisaurine azendohsaurid (Archosauromorpha: Allokotosauria) from two monodominant bonebeds in the Chinle Formation (Upper Triassic, Norian) of Arizona. Journal of Paleontology 96 Supplement S90:1–39. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/jpa.2022.49.

Parker, W. G., S. J. Nesbitt, A. D. Marsh, B. T. Kligman, and K. Bader. 2021. First occurrence of Doswellia cf. D. kaltenbachi (Archosauriformes) from the Late Triassic (middle Norian) Chinle Formation of Arizona and its implications on proposed biostratigraphic correlations across North America during the Late Triassic. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 41(3):e1976196. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2021.1976196.

Parker, W. G., S. J. Nesbitt, R. B. Irmis, J. W. Martz, A. D. Marsh, M. A. Brown, M. R. Stocker, and S. Werning. 2022. Osteology and relationships of Revueltosaurus callenderi (Archosauria: Suchia) from the Upper Triassic (Norian) Chinle Formation of Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona, United States. The Anatomical Record 305(10):2353–2414. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/ar.24757.

Rasmussen, C., R. Mundil, R. B. Irmis, D. Geisler, G. E. Gehrels, P. E. Olsen, D. V. Kent, C. Lepre, S. T. Kinney, J. W. Geissman, and W. G. Parker. 2020. U-Pb zircon geochronology and depositional age models for the Upper Triassic Chinle Formation (Petrified Forest National Park, Arizona, USA): implications for Late Triassic paleoecological and paleoenvironmental change. GSA Bulletin 133(3-4):539–558. doi: https://doi.org/10.1130/B35485.1.

Reyes, W. A., W. G. Parker, and A. D. Marsh. 2021. Cranial anatomy and dentition of the aetosaur Typothorax coccinarum (Archosauria: Pseudosuchia) from the Upper Triassic (Revueltian–Mid Norian) Chinle Formation of Arizona. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 40(6):e1876080. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.2020.1876080.

No comments:

Post a Comment