It's that time again, when another titanosaur makes an introduction. Today we have Jiangxititan ganzhouensis, from the late Late Cretaceous of southeastern China. As a disclaimer, I tend to reserve my judgment with East Asian titanosauriforms, who have a tendency to play coy about their phylogenetic relationships. However, J. ganzhouensis is interesting on its own terms, whether or not it is within that charmed circle of "Andesaurus delgadoi + Saltasaurus loricatus".

|

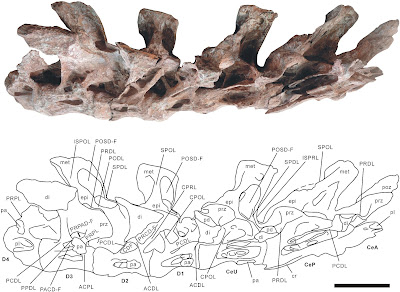

| A lateral view of the type vertebrae of Jiangxititan ganzhouensis, dorsals on left, cervicals on right; scale is 20 cm (8 in) (Figure 3, Mo et al. 2023, which see for legend) (CC BY-NC-ND-4.0). |

Genus and Species: Jiangxititan ganzhouensis. The genus name refers to Jiangxi Province and the species name refers to Ganzhou City, the fossil locality (Mo et al. 2023). This leads to something like "Jiangxi titan from Ganzhou City". A digression: Anybody else notice that Chinese dinosaur names are very frequently geographic in origin, rather than mythological, anatomical, or honorific?

Citation: Mo, J.-Y., Q.-Y. Fu, Y.-L. Yu, and X. Xu. 2023. A new titanosaurian sauropod from the Upper Cretaceous of Jiangxi Province, southern China. Historical Biology (advance online publication). doi: https:10.1080/08912963.2023.2259413.

Geography and Stratigraphy: The type and only known specimen came from the Maastrichtian-age Nanxiong Formation of Tankou Town, Nankang County, Ganzhou City, Jiangxi Province, southeastern China (Mo et al. 2023).

Holotype: NHMG 034062 (Natural History Museum of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, Nanning, China), 12 articulated bones from the base of the neck (three posterior cervicals, four anterior dorsals, two cervical ribs, and three dorsal ribs) (Mo et al. 2023).

J. ganzhouensis has a frustrating holotype. There are seven articulated vertebrae with attached partial ribs, enough associated material (and in good enough shape) to prompt the question "well, where's the rest of it?". It just looks like there should be more; it can't just be a chunk of the base of the neck, can it? (Unfortunately, yes, it can.) The authors do not go into detail on the circumstances of discovery, except to note it was recovered during construction work; we can always hope that another part of the skeleton is waiting to be discovered nearby.

It's kind of a cliché that titanosaurs are known from vertebrae and nothing else. In this case, the cliché mostly fits, but J. ganzhouensis goes out of its way to make a memorable impression. The centra are vertically compressed to an almost comical degree, but this does not appear to be primarily taphonomic (there is some taphonomic deviltry going on, but it mostly affects the left side). The neural spines are divided, as in Opisthocoelicaudia skarzynskii, but the spread of the division is extreme, with the spines very low rather than sticking up; the visual effect is as if J. ganzhouensis had made space to stack another vertebral column in the bifurcation. The spines are inclined anteriorly on the cervicals but vertically to slightly posteriorly on the dorsals. The neural arches are low, and features that would normally be placed facing dorsally and laterally just face laterally here. The one relatively complete dorsal rib appears to relatively short and slender (Mo et al. 2023). Comparison of vertebral sizes with O. skarzynskii indicates J. ganzhouensis was in the same general bracket (provided the rest of it wasn't radically different).

|

| How low can you go? An anterior dorsal of J. ganzhouensis (F) compared to Opisthocoelicaudia (A), Camarasaurus (B), Apatosaurus (C), Diplodocus (D), and Dicraeosaurus (E); scale 20 cm (8 in) (Figure 11 in Mo et al. 2023) (CC BY-NC-ND-4.0). |

We can proceed with confidence that J. ganzhouensis is not going to be mistaken for any other known sauropod represented by posterior cervicals or anterior dorsals. What exactly was it? The phylogenetic analysis of Mo et al. (2023) places it deep within Lognkosauria with its new best friend Mongolosaurus haplodon. Both of these are interesting points because Lognkosauria is famously a club for large South American titanosaurs and M. haplodon has a long history of shunning commitment. (Gannansaurus sinensis, from the same formation as J. ganzhouensis, also makes a guest appearance and remains firmly outside of Titanosauria, persisting as a rare late Late Cretaceous non-titanosaur.) Whether it remains in Titanosauria or gravitates out like various other putative East Asian titanosaurs, J. ganzhouensis will retain those distinctive vertebrae.

References

Mo, J.-Y., Q.-Y. Fu, Y.-L. Yu, and X. Xu. 2023. A new titanosaurian sauropod from the Upper Cretaceous of Jiangxi Province, southern China. Historical Biology (advance online publication). doi: https:10.1080/08912963.2023.2259413.

I recently published a blog post explaining why Gannansaurus is almost certainly a titanosaur and not closely related to Euhelopus:

ReplyDeletehttps://sauropoda.blogspot.com/2023/09/is-gannansaurus-non-lithostrotian.html

As I explain in this post, the "K"-shaped laminae pattern on the mid-dorsal vertebrae of Euhelopus and Gannansaurus is also present in the lithostrotian titanosaur specimen PIN 3837/P821 from the Nemegt Formation and thus evolved independently in more than one somphospondylan clade. Although the holotypes of Gannansaurus sinensis and Jiangxititan ganzhouensis don't overlap with each other, the slightly opisthocoelous nature of the anterior caudals of Sonidosaurus and the presence of mild procoely in the anterior caudals of Qinlingosaurus despite both taxa being about the same age suggests that Gannansaurus and Jiangxititan are more likely than not to be distinct.