No sooner do I finish one titanosaur post when another new one shows up for its turn in the spotlight. Our latest guest, Chadititan calvoi, is another from the hallowed titanosaur stomping grounds of Late Cretaceous Patagonia. For anyone who feels the need to chuckle over the meme factor in the name, the jump break should present an opportunity to get it out of the system. (Ironically enough, Chadititan is noted for its small body size and slender limbs.) If you don't know the meme, feel free to ignore it and cross the jump break just the same.

Have we all made it across in one piece? Great!

Genus and Species: Chadititan calvoi. The first part of the genus name is derived from "chadi", the Mapundungum word for salt, in reference to a nearby salt flat. The species name honors the late paleontologist Jorge Calvo, a frequent contributor on titanosaurs and the originator of Rinconsauria (Agnolín et al. 2025). Putting it all together we get something like "Calvo's titan of the salt".

Citation: Agnolín, F., M. Motta, J. G. Marsá, M. Aranciaga-Rolando, G. Alvarez-Herrera, N. Chimento, S. Rozadilla, F. Brissón-Egli, M. Cerroni, K. Panzeri, S. Bogan, S. Casadio, J. Sterli, S. Miquel, S. Martínez, L. Pérez, D. Pol, and F. Novas. 2025. New fossiliferous locality from the Anacleto Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian) from northern Patagonia, with the description of a new titanosaur. Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales nueva serie 26(2): 217–259.

Usually I just put up the citation here and that's that, but there were a few things I wanted to mention in this case. For one, the header of the article uses 2024 instead of 2025, which suggests a 2024 publication was anticipated. (Or that there was simply a typo, but that's not as interesting.) If you're wondering why there are 18 coauthors, this is not just a publication on a titanosaur, but on a site with a lot of things beside just the sauropod. In that respect, it's like Novas et al. (2019), the publication that described Nullotitan glaciaris (22 coauthors). Finally, at the moment my antivirus hates the journal's website due to a security certificate issue, so if anyone from the website is reading this, that might be something to check on.

Geography and Stratigraphy: The fossils of C. calvoi were discovered at a locality on the Marín farm, about 10 km (6 mi) southwest of General Roca in Río Negro Province, Argentina (Agnolín et al. 2025). The rocks pertain to the Anacleto Formation. Agnolín et al. cite a middle Campanian (78.6 ± 1.7 million years) maximum age for the formation following Gómez et al. (2022) (a little younger than I had it before, so I updated it in the spreadsheet). Aside from some Skolithos burrows in dune sandstone, most of the fossils at the Marín locality came from mudstones deposited in low-energy lake settings low in the local stratigraphic section. These fossils include material pertaining to bivalves, snails, gars, percomorph ray-finned fish, lungfish, turtles (many turtles), a croc, a pterosaur, an Aucasaurus-scale abelisaur with anatomy similar to Aucasaurus (which happens to hail from the Anacleto Formation, so I suppose I wouldn't be surprised to find out it is Aucasaurus), and a meridiolestid mammal (Agnolín et al. 2025).

Holotype: MPCN-Pv 1034 (Colección Paleontología de Vertebrados, Museo Patagónico de Ciencias Naturales "Juan Carlos Salgado", General Roca, Río Negro, Argentina), consisting of five proximal and four distal caudal vertebrae, the proximal end of the left pubis, the proximal end of the right ulna and both ends of the left, the distal right radius, both ends of the right femur, the proximal end of the left tibia and both ends of the right, both ends of the right fibula, and metapodials (Agnolín et al. 2025).

In addition to the holotype, assorted bones of other individuals are assigned to seven other MPCN-Pv catalog numbers (1035 to 1041). They're mostly examples of the same kinds of bones included in the holotype, except for a dorsal centrum, a coracoid, and identifiable metacarpals and foot bones, and are interpreted as "poorly preserved and incomplete skeletons... from the same stratigraphic level" (Agnolín et al. 2025).

|

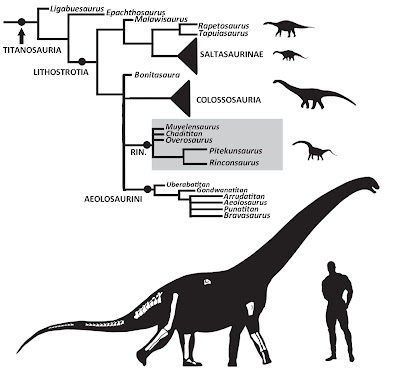

| Chadititan calvoi out for a stroll, plus simplified phylogeny. Figure 11 in Agnolín et al. (2025). CC-BY-3.0. |

As mentioned above, C. calvoi presents itself as a small, gracile titanosaur, with a body length estimated around 7 m (23 ft) and a femur about 73.5 cm (28.9 in) long (Agnolín et al. 2025). "Aha!" you say. "We're dealing with subadults!" No, these are apparently mature; they're just small titanosaurs (Agnolín et al. 2025). This range puts us in the general realm of Neuquensaurus australis, another Anacleto titanosaur, albeit much different anatomically. The caudals are relatively elongate but not particularly unusual as far as titanosaur caudals go; they are not well preserved, with broken processes. They are restored as forming a steep downward swoop from the hips before leveling off ("protonic tail posture") (Agnolín et al. 2025), as has recently been proposed for aeolosaurs (Vidal et al. 2021). The limb bones have little expansion at the ends (Agnolín et al. 2025). No osteoderms have been recovered (Agnolín et al. 2025). Of course, given the sparseness of osteoderms on known armored titanosaurs, it's entirely possible that C. calvoi *did* have them and they just weren't part of the preserved remains; they certainly had heads, necks, and complete shoulder and pelvic girdles as well.

A phylogenetic analysis found C. calvoi to be a rinconsaurian titanosaur, along with Muyelensaurus pecheni, Overosaurus paradasorum, Pitekunsaurus macayai, and Rinconsaurus caudamirus (Agnolín et al. 2025). The first and the last of that list are hardly surprising, as M. pecheni and R. caudamirus are phylogenetically inseparable. The other two are more notable company, as O. paradasorum is usually an aeolosaur and P. macayai, like most titanosaurs, has commitment issues. On the other hand, rinconsaurs and aeolosaurs have some similarities and P. macayai shared with R. caudamirus an inability to decide how it wanted its caudals to articulate. Together they make a clade of smallish, gracile titanosaurs.

By my count, C. calvoi makes for eight named titanosaurs in the Anacleto Formation with some claim to validity. In addition to our present guest, there are Antarctosaurus wichmannianus (big with flat face), Barrosasaurus casamiquelai (big and known from a few dorsals), Laplatasaurus araukanicus (big and known from a tibia and fibula), Narambuenatitan palomoi (medium and known from much of a skeleton), Neuquensaurus australis (little, intriguing combination of delicately pneumatic body and robust limbs), Pellegrinisaurus powelli (big and known mostly from a tail), and Pitekunsaurus macayai (small and known mostly from verts) (well, and Loricosaurus scutatus and "Titanosaurus" robustus, but they're probably just N. australis). This roster may vary depending on your stratigraphic interpretations, but the point still stands. It's rather unlikely that they're all growth stages or morphs of one obnoxiously variable species, but gee, that's a lot of titanosaurs, and they ain't exactly Darwin's finches in the Galápagos Islands. Inconveniently, there is limited overlap among them, as can be gathered from the parenthetical asides, so we can only hope for more complete specimens. In fact, there just so happens to be a more complete Anacleto titanosaur, unnamed since the 1990s: MAU-Pv-AC-01, the Rincón de los Sauces titanosaur, missing only the legs (sorry, Laplatasaurus) and left arm. Any day now...

References

Agnolín, F., M. Motta, J. G. Marsá, M. Aranciaga-Rolando, G. Alvarez-Herrera, N. Chimento, S. Rozadilla, F. Brissón-Egli, M. Cerroni, K. Panzeri, S. Bogan, S. Casadio, J. Sterli, S. Miquel, S. Martínez, L. Pérez, D. Pol, and F. Novas. 2025. [dates in article indicate a 2024 publication was anticipated] New fossiliferous locality from the Anacleto Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian) from northern Patagonia, with the description of a new titanosaur. Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales 26(2): 217–259.

Gómez, R., M. Tunik, S. Casadio, N. Canale, G. Greco, M. A. Baiano, D. Pino, A. Baez, and S. Pereira da Silva. 2022. Primeras edades U-Pb en circones detríticos del Grupo Neuquén en el extremo oriental de la Cuenca Neuquina (Paso Córdoba, Río Negro). Latin American Journal of Sedimentology and Basin Analysis 29(2): 67–81.

Novas, F., F. Agnolin, S. Rozadilla, A. Aranciaga-Rolando, F. Brissón-Eli, M. Motta, M. Cerroni, M. Ezcurra, A. Martinelli, J. D'Angelo, G. Álvarez-Herrera, A. Gentil, S. Bogan, N. Chimento, J. García-Marsà, G. Lo Coco, S. Miquel, F. Brito, E. Vera, V. Loinaze, M. Fernandez, and L. Salgado. 2019. Paleontological discoveries in the Chorrillo Formation (upper Campanian-lower Maastrichtian, Upper Cretaceous), Santa Cruz Province, Patagonia, Argentina. Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales 21(2): 217–293.

Vidal, L. D. S., P. V. L. G. da Costa Pereira, S. Tavares, S. L. Brusatte, L. P. Bergqvist, and C. R. dos Anjos Candeiro. 2021. Investigating the enigmatic Aeolosaurini clade: the caudal biomechanics of Aeolosaurus maximus (Aeolosaurini/Sauropoda) using the neutral pose method and the first case of protonic tail condition in Sauropoda. Historical Biology 33(9): 1836–1856. doi:10.1080/08912963.2020.1745791.

No comments:

Post a Comment