Obviously the first and most important thing to do is to check if Tweet et al. (2008) is cited, and if so, how it made out. We will all no doubt be relieved to know that it is well-represented. It's an odd feeling (or terrifying; it's one of those two) to realize my own paper is being cited as an authority of some kind. (It's also odd or terrifying to realize that the 2008 paper is 12 years old. Since when do I have a paper that's 12 years old? What's next? 13? Pshaw!*)

*For unrelated reasons I just had a look at the file for my thesis. It's only 67 pages and fewer than 16,000 words. Mein Gott, I would have sworn it was three times that long when I was working on it. Maybe the file has shrunk. Is that a recognized computer bug?

|

| The layout of the Borealopelta and its gut contents (Figure 1 in Brown et al. 2020, which see for caption). CC-BY-4.0. They have nicer figures than Tweet et al. (2008), too. |

Enough levity. Brown et al. (2020) is important for several reasons. Their specimen indeed has the best case for herbivorous nonavian dinosaur gut contents, being a basically intact bloat-and-float rather than something stuck in a fluvial setting. Furthermore, the plant material is well-preserved, which allows additional angles of study that weren't open for, say, Leonardo. Beyond this, the authors have taken the opportunity to go over the criteria and methodology for determining whether something is gut contents and not just coincidental plants. They prepared a set of 16 criteria, some new, others culled or modified from other gut content papers. Is this the final word on the subject? No; every scheme can be refined. It's certainly handy, though, and the most comprehensive to date. I did notice that overall their focus was on biology, whereas Tweet et al. (2008) out of necessity focused on taphonomy (the science of showing how beloved pop-paleo concepts like pack-hunting dromaeosaurs are, at best, drastic over-interpretations of the actual data).

Because there are so few other reports of gut contents in herbivorous classic dinosaurs, there's also room for a table assessing these existing reports (Table 1). The potential record of Liaoningosaurus doesn't get much comment and is not included in Table 1, perhaps because, strictly speaking, it would not be a herbivorous record. All of the other herbivore reports are there, although presumably the timing didn't allow an opportunity to add Uhl (2020)'s reassessment of the Senckenberg "Trachodon" (which I have not seen yet, either). If you're curious about how Brown et al. placed various records as "equivocal", "not supported", etc., these are based on the 16 criteria, and the exact scores for several specimens (including Leo, coming in with 7 points) are found in the supplementary material.

|

| Two photomicrographs of the gut contents (Figure 5 in Brown et al. 2020). Per caption, "In both, (a) sporangia, (b) leaf cuticle with stomata present, (c) gastroliths, (d) woody material, (e) leaf cross-sections and (f) sclerenchyma. Top, slide 3; bottom, slide 6. Scale bars = 200 µm." CC-BY-4.0. |

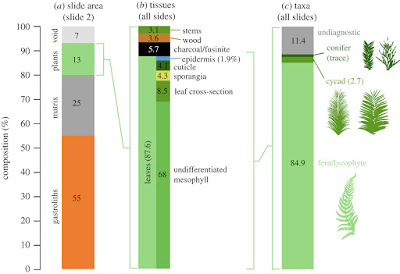

Brown et al. (2020) found the plant material inside Borealopelta to consist overwhelmingly of leaf tissues (87.6%), and in turn 84.9% of that 87.6% pertains to leptosporangiate ferns, which works out to 74.3% overall being fern leaf tissues. The true figure could be larger, because another 11.4% of the leaf sample was undiagnostic. This Borealopelta certainly seems to have had a fondness for leptosporangiate ferns at the time it died, which makes anatomical sense: we're talking about a low browser, after all. Minor quantities of cycad/cycadeoid and conifer leaves were also present, as well as stems, wood, and charcoal. Anatomical features of the plants suggest that the animal died sometime between late spring and mid-summer. Brown et al. propose that the charcoal got there via the animal eating in a recently burned area, which may have been favorable for a low-browsing fern-eating animal (ferns can show up early in a post-fire succession). There's a great hook in here for paleoartists: depicting the nodosaur in a fern carpet growing among burned-out trunks and logs.

|

| Figure 6 in Brown et al. (2020), showing the breakdown of one of the slides. CC-BY-4.0. |

Plant material is reported as sheared, by a combination of the teeth and what are interpreted as small gastroliths. I would have liked more discussion of the gastroliths, which measured approximately 2 mm to 2 cm across (or quite a bit smaller than the "gastroliths" available for purchase in rock shops). The authors suggest that these were within a posterior muscular stomach, as seen in birds and crocodilians. Interestingly, both this specimen and the Kunbarrasaurus ("Minmi sp.") specimen with apparent gut contents have them in the left "lumbar" region, which the authors suggest was the actual position of this posterior muscular stomach.

References

Brown, C. M., D. R. Greenwood, J. E. Kalyniuk, D. R. Braman, D. M. Henderson, C. L. Greenwood, and J. F. Basinger. 2020. Dietary palaeoecology of an Early Cretaceous armoured dinosaur (Ornithischia; Nodosauridae) based on floral analysis of stomach contents. Royal Society Open Science 7(6):200305.doi:10.1098/rsos.200305.

Tweet, J. S., K. Chin, D. R. Braman, and N. L. Murphy. 2008. Probable gut contents within a specimen of Brachylophosaurus canadensis (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous Judith River Formation of Montana. Palaios 23(9):624–635.

Uhl, D. 2020. A reappraisal of the "stomach" contents of the Edmontosaurus annectens mummy at the Senckenberg Naturmuseum in Frankfurt/Main (Germany). Zeitschrift der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Geowissenschaften 171(1):71–85. doi:10.1127/zdgg/2020/0224.

No comments:

Post a Comment